Global investment in Renewable Energy (RE) is on a strong upward trend, reaching a new record of $386 billion in the first half of 2025, a 10% increase from the previous year. Despite some regional declines and a slowdown in utility-scale solar, the sector is being supported by factors like government policies and grid infrastructure investment. Overall, investment is now nearly double the amount going to fossil fuels.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Investment Report 2025, the global energy investment is projected to reach a record $3.3 trillion in 2025, with clean energy technologies attracting $2.2 trillion (as said above), which is double the $1.1 trillion expected for fossil fuels.

Solar PV is expected to lead this growth, with investment in the technology forecast to reach $450 billion in 2025, and battery storage investment surpassing $65 billion this year.

Finance for both onshore and offshore wind increased by about a quarter in the first half of 2025. Investment in enabling technologies like batteries also grew significantly in 2023.

Around three-quarters of the $470 billion in future clean energy finance announced since January 2025 is targeted towards electricity grids, which have been a bottleneck for renewable energy deployment.

Glimpses of the growth of REs across the globe

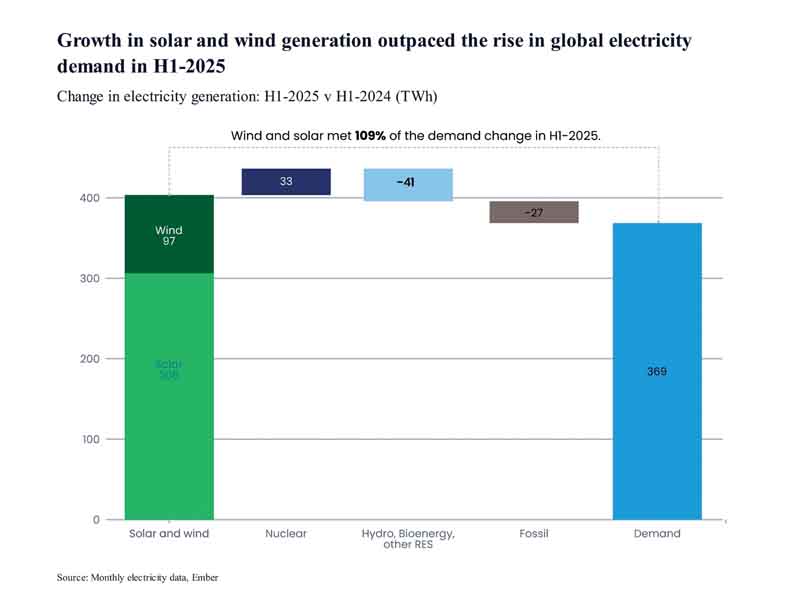

According to the most recent report from Ember (an energy think tank that aims to accelerate the clean energy transition with data and policy) titled, “Global Electricity Mid-Year Insights 2025, “The increase in solar and wind power outpaced global electricity demand growth in the first half of 2025. Solar alone met 83% of the rise, with many countries setting new records. Fossil fuels remained mostly flat, with a slight decline. Fossil generation fell in China and India, but grew in the EU and the US.”

Five significant points from Ember’s observation

- Global electricity demand grew by 2.6% (+369 TWh) in the first half of 2025. This increase was more than met by increases in solar (+306 TWh, +31%) and wind (+97 TWh, +7.7%) generation, with solar alone covering 83% of the rise. Hydro fell significantly while bioenergy output dipped slightly, and nuclear rose modestly, while overall fossil generation fell marginally (-0.3%).

- Solar grew by a record 306 TWh (31%) in the first half of 2025. This increased solar’s share in the global electricity mix from 6.9% to 8.8%. China accounted for 55% of global solar generation growth, followed by the US (14%), the EU (12%), India (5.6%) and Brazil (3.2%), while the rest of the world contributed just 9%. Four countries generated over 25% of their electricity from solar, and at least 29 countries surpassed 10%, up from 22 countries in the same period last year and only 11 countries in H1-2021.

- A strong rise in solar, and to a lesser extent wind, led to renewables overtaking coal generation for the first time on record in the first half of 2025. Renewables grew by 363 TWh (+7.7%) to reach 5,072 TWh, while coal generation fell by 31 TWh to 4,896 TWh. As a result, renewables’ share of global electricity rose to 34.3% (from 32.7%), while coal’s share fell to 33.1% (from 34.2%).

- Global fossil fuel generation fell slightly in the first half of 2025, down 27 TWh from the same period last year. Among major economies, fossil fuel generation decreased in China and India, where clean generation outpaced demand growth. By contrast, in the US, clean sources did not keep pace with demand rise, so fossil generation increased. In the EU, both coal and gas inched up to offset lower wind, hydro and bioenergy output.

- Despite global electricity demand rising by 2.6%, emissions fell slightly by 12 MtCO2 in the first half of 2025. Declines in China (-46 MtCO2) and India (-24 MtCO2) reflected clean generation growth outpacing demand. By contrast, emissions increased in the EU (+13 MtCO2) and the US (+33 MtCO2) compared to the same period last year.

Trend of global investment in RE

Based on a consensus among international energy agencies, while significant progress has been made, the world is not on track to meet renewable energy investment goals needed to limit global warming to 1.50C. The necessary energy transition is ‘off-track’, requiring a massive, rapid, and equitable increase in investments to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change.

The trend of global investment in renewable energy is characterised by continued, strong growth that is primarily led by solar power. However, this expansion is highly concentrated, with disparities in funding and deployment across different regions. The total investment still falls short of the level required to achieve net-zero targets.

Although, in 2025, the amount going to clean energy and efficiency is twice that for oil, natural gas, and coal, according to a McKinsey report, the net-zero transition requires roughly $1 trillion in additional annual spending on top of baseline expectations.

What will be the impact of disparities in global RE spending

Disparities in global renewable energy spending may decelerate the desired effect by 2050 by creating a ‘decarbonisation divide’ between developed and developing nations. Today, while richer countries have accelerated investment, many developing countries are facing immense barriers, including a high cost of capital, inadequate infrastructure, and higher perceived risk for private investors. This is begetting a situation of uneven transition. If the process continues in the same way, some developing nations will have to rely on fossil fuels for longer, undermining global emission control targets. As a result of that we have already started experiencing:

- Persistent fossil fuel reliance in developing nations: Disproportionate spending forces many developing countries to continue using fossil fuels to meet growing energy demand.

- Exacerbated climate risks: A slower, less comprehensive global energy transition intensifies climate change impacts, which disproportionately affect developing countries. Global CO2 emissions are rebounding from pandemic-induced shocks, falling far short of the reductions needed to stay on track for the 1.5°C Paris Agreement target.

- Reinforced global inequalities: The uneven transition may reproduce historical power dynamics, leaving developing countries at the bottom of the value chain for green technology. Countries with high renewable resource potential may see other nations accumulate wealth from those resources, leading to potential exploitation and continued inequality.

- Fragmented regulatory landscape: Varying regulatory frameworks across countries create a challenging investment environment. The lack of unified standards and international cooperation can make it difficult for investors to finance renewable projects in riskier markets.

- Stunted economic development: Developing nations that fall behind risk are suffering from reduced economic resilience and competitiveness. A prolonged reliance on imported fossil fuels exposes them to volatile price swings and diverts domestic capital away from productive investments.

A few steps to improve the situation

To remove disparities from investments in renewable energy, a combination of targeted policies, financial mechanisms, and systemic reforms is necessary. These measures must address the disproportionate access to capital, technology, and stable governance that favours developed economies and large-scale projects over developing nations and marginalised communities.

Even in 2025, numerous countries are continuing to provide fossil fuel subsidies, despite calls for their phase-out, with significant levels observed in G7 nations like Germany, Japan, and France, as well as major fossil fuel-producing countries such as Saudi Arabia and Libya. Subsidies are often implemented to stabilise economies, control high energy prices, or support energy-intensive industries, leading to a complex global landscape where a substantial portion of the $1.1 trillion in fossil fuel support in 2023 has no planned end date. Rethinking and re-planning in this regard are very urgent.

Thus, it is high time to be aware and redirect easy financing towards risk-prone markets – as no risks can be more severe than the risk of our existence.

By P. K. Chatterjee (PK)